[Ancient] patriarchal writers tended to emphasize the soul called "breath," pneuma, since this was the kind of soul that could be given by a father. Brahman fathers gave their children breath-souls as opposed to the souls of blood, heart, name, flesh, mind, shade, etc., contributed by their mothers.

Barbara Walker / Women's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets

I was a late bloomer. But anyone who blooms at all, ever, is very lucky.

Sharon Olds

I'm a little like Flaubert, who when he looked at a young girl saw the skeleton underneath.

Sally Mann

the flesh soul | the new new feminism

Sharon Olds/ First Hour

That hour, I was most myself. I had shrugged

my mother slowly off, I lay there

taking my first breaths, as if

the air of the room was blowing me

like a bubble. All I had to do

was go out along the line of my gaze and back,

feeling gravity, silk, the

pressure of the air a caress, smelling on

myself her creamy blood. The air

was softly touching my skin and mouth,

entering me and drawing forth the little

sighs I did not know as mine.

I was not afraid. I lay in the quiet

and looked, and did the wordless thought,

my mind was getting its oxygen

direct, the rich mix by mouth.

I hated no one. I gazed and gazed,

and everything was interesting, I was

free, not yet in love, I did not

belong to anyone, I had drunk

no milk yet--no one had

my heart. I was not very human. I did not

know there was anyone else. I lay

like a god, for an hour, then they came for me

and took me to my mother.[1]

The photographs of her children: it takes a long time to get to them. I have to traverse cultural politics, social controversy, and treacherously half-sunken rafts (agendas) of critical convention. It's because I'm reading Sharon Olds that I revisit Sally Mann's 1992 work, Immediate Family. The spoiling-for-a-fight criticism of the two artists becomes mingled, inter-textual in my head, as do the answers and questions they offer in interviews. These are serious, wryly observant, confidently intelligent women. In their writing and photographs a boundary is being crossed, and it has less to do with decency, modesty or nudity than one might think from the invective each of these artists has accumulated with her body of work.

There is a link, a shift signaled in Mann's images and Olds' poetry, toward an almost unrecorded truth, a taboo that goes deeper than the impropriety and licentiousness imputed to both. In different ways, each artist presents motherhood as primary, primal, and shamanic, and each offers a path of the individual self as specifically empowered by having been made flesh from flesh.

In both artist's work, woman as origin of life is a foundational assertion from which the individual's subsequent journey of identity and self realization draws its compelling force. Neither stakes a territory enjoining or refuting the social conventions of mothering; instead the work itself embodies a critique of the subjugation or elision of the extraordinary fact of the physicality of self and especially woman as source of this physicality; in this sense, the work of both Olds and Mann "does what it says" as a method of effectively "saying what it means".

This "doing" of embodiment is thus demonstrated as a strategy for reclaiming agency in situations where "arguing" the point cannot lead to liberation of perspective or fresh understanding because the particular expression required for clarity is already ruled out by currently held denotations of the terms, definitions enforced by the very authority under question.[2]

Several examples quickly convey the striking parallels between Olds' and Mann's work. There's an artistic and numinous resonance between Mann's photographs of and Olds' poems about their children. Olds' Six Year Old Boy, for example, with its reference to her young son

asleep on the back seat

his wiry limbs limp and supple

except where his hard-on lifts his pajamas like the

earth above the shoot of a bulb [3]

Sally Mann/ The Wet Bed

There's a specific compounding of the unrestrained, responsive physiological body with the presence of the child as a sovereign being, as Life.

Similarly, mirroring Mann's daughter in the photograph Jessie at 6, Olds' daughter is figured acorn-like, simultaneously fruit and seed in Olds' Pre Adolescent in Spring. The girl is able to call forth in a single motion both the heat of her own conception and the woman she will become as the poet follows the life pulse of her daughter's hair warming in the sun:

dark as the

packed floor of the pine forest,

its hot resin smell rising like a

smell of sex. She leaps off the porch and

runs on the grass her buttocks like an unripe

apricot.[4]

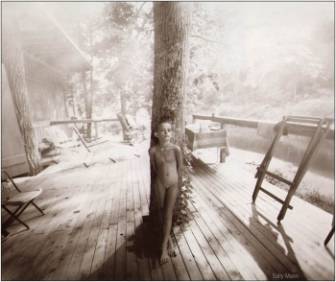

Sally Mann/ Jessie at 6

It isn't only the explicit presence of nascent sexuality, it's the coincident and persistent foregrounding and grounding of motherhood, womanhood, life, and poetics in physicality, and an inherent privileging of embodied perspective.

In Olds' work, this unity is conveyed as life itself; her children are metonymically allied with, identified as, forces of Nature. It is a Nature, however, a priori to social and textual subjugation as metaphor. As poet and mother, Olds observes in her children the autopoiesis[5] of life: there is no separation of body and self.

In this sense, Olds promulgates her writing and its politics from an epistemology that grounds itself in advance of the presupposition of dualism and its subsequent "mind/body" problem. By articulating self as arising through the experiences of the organism in its environment, Olds eludes the conventions of Cartesian mechanism and all that is entailed by its metaphors. Instead of, "I think, therefore I am," Olds states simply "I am this." [6]

Through all the contested identity of gender, sexuality, and self, artists who would challenge the status quo and its punishing social consequences have devoted lifetimes against its confining definitions and prejudice. Olds', while being critically accused of vulgarity and sensationalism, bases her argument in what she considers to be the highest truth: her physically lived experience. There is no godhead from whom falls the soul to the body. Whatever else, Olds' primary argument is that it is woman who gives birth, that it is sex which engenders life, that we are in fact sex itself.

and how I am

one-fourth him, a brutal man with a

hole for an eye, and one-fourth her,

a woman who protected no one. I am their

sex, too, their son, their bed, and

under their bed the trap-door to the

cellar, with its barrels of fresh apples, and

somewhere in me too is the path

down to the creek gleaming in the dark, a

way out of there.[7]

Olds liberates the meaning and meaningfulness of life from derangement in dominance politics. Brutality in a world devoid of compassion coexists with fresh possibility, the tree of life filling whole barrels with samizdat apples. Her poetry reveals life propagating, flourishing in dynamic rather than linear processes. It is an embodiment which valorizes the body.[8] Rather than denigrating the body as temporal, or seeking to transcend the senses as base distractions, sinful or misleading, Olds reclaims the body, from both fundamentalism and pornography, as sacred. In this world view, the spiritual tradition of dharma is reborn as tantric, that is to say, a path which is the body. Living the body achieves "a way out of" darkness.

Embodiment is the consistent "from where" of Olds writing. Though she takes her children as subjects for her work, their lives are never coy reflections of herself as a good parent. When Olds writes a poem about her son's broken arm, there's no socially conventional display of sentiment to impede the vivid

bones twisted like white

saplings in a tornado, tendons

twined around each other like the snakes on the

healer's caduceus.

...

fine joint that

used to be thin and elegant as

something made with Tinkertoy, then it

swelled to a hard black anvil,

softened to a bruised yellow fruit[9]

Sally Mann/ Bloody Nose

Through embodied motherhood, both Olds and Mann present powerful matriarchal eschatologies. Olds focuses on motherhood as an embodied state rather than socially constructed and bestowed (and therefore earned) status. She writes of the mother as a mythic figure of shamanic power, one who can cross between worlds. In That Moment, Olds describes a woman who stands alone in a field, her children on the other side of a fence, waiting for her, her "body swinging suddenly" as she brings them through her womb from the ether into flesh created from her flesh, into bodies of their own:

the journey from the center of the field to the edge

or the cracking of the fence like the breaking down of the

borders of the world, or my stepping out of the

ploughed field altogether and

taking them in my arms

...

and I stood with them outside the universe

and then like a god I turned and brought them in[10]

Sally Mann/ The Ditch

Sally Mann's work has earned her castigation for exploiting her children. Writing about Mann for the Times Literary Supplement, Julian Bell felt himself sufficient to instead review Mann as a mother, commenting that her photography, "seems a rotten way to bring them up."[11] Janet Malcolm sums up the critical milieu with irony:

What mothers who photograph their children normally try to capture (or as the case may be, create) are the moments when their children look happy and attractive, when their clothes aren't smeared with food, and they aren't clutching themselves. Mann, abnormally, takes pictures of her children looking sulky, angry, and dirty, displaying insect bites or bloody noses, and clutching themselves. Reviewers of Immediate Family and of the exhibition that preceded its publication harshly rebuked Mann for her un-motherliness and pitied the helpless, art abused children. "At moments when any other mother would grab her child to hold and comfort, Mann must have reached instead for her camera, " one reviewer wrote.[12]

Constructing "good" motherhood as "earned" and publicly differentiable from "bad" motherhood which is punishable, provides social and legal instruments for policing women. It is women as mothers through whom children are censored into socially preferable characters, and this "downsizing" comes though a cost to undeformed ego development, where neurotic self vigilance assures the reproduction of socially acceptable self images. In the common parlance, it is better to fit in than to stand out.

The promotion of the concept of mothering as of a higher conceptual and ethical status than the physiological capability to engender a life is in a sense a brilliant and insidious misogyny. It is adequate, even necessary and good, to agree socially that the responsibility for raising a child can be successfully assumed by anyone who has a will and a heart to do it ( or who can unfortunately get away with doing it heartlessly).[13]

The idea that children belong more to society than they do to their biological mothers is generally presented as action on the child's behalf and never as domestic terrorism. It should be observed, however, that it remains impossible to add citizenry to the machinery of any culture unless mothers are coerced into forming said citizens from their offspring: it is the most embedded form of colonization. The focus on the social contract of "mothering", rather than on the primordial mother, relieves a pervasive cultural anxiety about the undeniable power of women to form and grow new life within their own bodies, to actually make a new flesh from their own flesh, gestate and birth a being separate from themselves, a new life.[14]

The idea that a mother might have other thoughts about her children, their liberties and need for self expression, about what is life giving, is socially monitored. The charge of pornography was rabid enough for Mann to invite an FBI agent to view her work before she showed it publicly.[15] If such a charge proved viable against Mann, she could not only lose control of her work, she could lose the custody of her own children.

And yet. "The camera is magnetized by kinship," writes Reynolds Price.[16] "If a count could be taken of all the images captured by the camera since photography was invented, I'm sure that images of family would account for a high percentage of the staggering total say, ninety percent of the hundreds of millions." One afternoon while staring for the twentieth time at Virginia Mann in the photographs Last Light, Virginia at 3, Virginia at 4, I was struck by the familiarity of the gaze. I began to think of particular snapshots of my own son, pictures I'd taken of him at that age.

We were living on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, on a city block hemmed by a chain link fence of bumper to bumper parking and six lanes of busy traffic. I was single, working full time, writing when I could. We had little in the way of resources. I didn't own a car or even have a driver's license. But I was a young mother, physically quite strong, and the green line stopped in front of our building. On my days off, if the weather was good, I'd carry my son and his tricycle downtown on the subway.

We considered the Public Gardens our back yard, whiling hours feeding the ducks, and following each other among the flower beds through the green lawns. Once tired of the park, we'd retire down Charles Street to Il Dolce Momento for Orangina and coffee. I'd write and my son would draw; we'd watch people together. Sometimes we took pictures of each other. The photographs were a kind of "doing" together; not souvenirs, but traces, artifacts of a way of life in which we were engaged, which was: being specifically us.

What I saw in Sally Mann's children was the expression of that intimacy, unfamiliar to persons who never spend time alone with children, never collaborate, never ruminate at length about the origin of various articles of clothing, other people's faces, the taste of one kind of thing vs. another, who never compare the relative merits of colors, chairs, sneakers, subway stations, dogs. I eventually encountered a comment from Mann that seemed to validate what I felt a connection to in the photographs:

It's not like these kids had to keep some shred of personal dignity squirreled away from their prying Mom's camera lens. They were -- and are still -- active participants in the art-making that goes on all around them. Art is in every aspect of our everyday life -- in the gardens we have designed around the house, in what we put on our walls, in the pumpkins we cut for Halloween. And any parent knows that you can't force a child to make art; they have to cooperate, they have to want to be part of the process.[17]

Maybe some people who don't have children can't imagine their agency, or those for whom their children are small demanding charges whose wishes are never considered in the clear light of a child's own judgment and articulation; wistfulness, soulfulness, violence, ambitions, inchoate longings are overlooked, requests are entertained as rude instruments for negotiation - be good [do as I say] and I will do this, give you that. In short, those for whom children are something foreign, for whom children's inner lives are a subject as muted and remote as their own. And maybe this abandonment is the true condition of nostalgia, the insistence on a false and indefatigable innocence based on repression, on censorship, on silence.

The lie that is forced upon children in the guise of celebrating innocence is perpetrated by dualism. That one cannot be hostile and loving, self and belonging, pure and sexual, one must be either/ or. What I saw in the photographs Mann took of her children is a circle of gaze which defies this mandate, which offers back a wholeness that exist before paradox, before good and bad become mutually exclusive and externally defined labels on experiences.

They are collaborators, and their instinctive originality is based in unhindered self esteem. The look in the eyes of her children states clearly that they are looking at themselves primarily and that our gaze as a viewers comes secondarily to their imaginations, after the healthy satisfaction of seeing themselves exactly as they wish to be seen by themselves. Rather than shaming this self regard, Mann as mother and artist gives them the opportunity of introjecting their own images, of being the labile objects of their own satisfaction. In a sense, in her work Mann embodies the shamanic mother of Olds' That Moment: through her lens she brings her children into the bodies they ask for, and into a sense of fully embodied self.

When we made these pictures, the kids knew exactly what to do to make an image work: how to look, how to project degrees of intensity or defiance or plaintive, woebegone, Dorthea-Lange dejection. I didn't pry these pictures from them -- they gave them to me. Remember that and the images take on a wholly different meaning -- no deep psychological manipulations or machinations, just the straight-forward, everyday telling of a story.[18]

The primary identification of the person who sits for the portrait as the audience for that portrait, as the one who has been enabled by the portraitist to present themselves to their own satisfaction to the world, is constantly ignored in the critical reception of Mann's work. Her willingness to collaborate with them, to give them what they ask for and not to censor it is what is forbidden, for mothering above all is the task of socializing.

It is the father who breathes the life of industry and occupation into his sons and gives his daughters' hands in marriage, thus bestowing identity, membership in the broken world of opposites. Mothers are the agents by which "the child will have to be broken of its habit of trust in the world's benevolence."[19] Motherhood enjoined as socializing children, breaking children to submission and obedience within a dominant culture, is trauma veiled in sentiment and the postures of purity and innocence, of doing "what's good for them," and substituting this simulation as the natural and inborn state.

Mann defies the constructs of socially bestowed motherhood; it's for this she is vilified, for not subverting her children's pleasure in self into the soul eating limits of the world for which she is supposed to be "civilizing" them; she grants the flesh soul to her children. In her lens her children birth themselves again and again, with the confidence of those who know their self-interest is legitimate.

Sally Mann/ Emmet, Jessie, and Virginia