| volume 2 of london: 1970 april-december | work & days: a lifetime journal project |

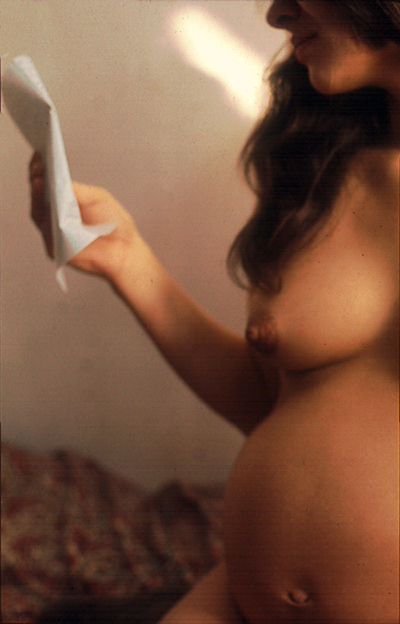

- photo Mafalda Reis - photo Mafalda Reis |

|

A scrappy journal with a lot of elisions. Volume 2 ends a few days before Luke's birth. In the nine months of my pregnancy Roy and I panic again and again. We escape from each other in our different ways. Part 1 we rush around Europe on the motorbike, I remember childhood. He runs an insurance scam, moves out briefly. Part 2 I hitchhike to Paris a couple of times to collect a French scholarship, and to Avignon to a film festival. In August I take Roy to Canada: to Kingston, to La Glace to meet my parents, and to my sister's commune at Winlaw in the Kootenays. Part 3, back in London, I begin my second year at the Slade. In autumn there's a sweet brief truce when Roy is sick in bed with hep B he caught from one of his women. In this volume the struggle with Roy is at least as desperate as the struggle with my two previous men, but the tone feels quieter, deeply centred at times. "I do know the peace and elation and certainty that collect in me when fear and anguish have been hard on me." Mentioned: Mary Epp, Ed Epp, Roy Chisholm, Olivia Carmichael, Don Carmichael, Buddy Hardy, Margaret Gosley and Shoshanna, Mafalda Reis, Catherine Chisholm, Maria Reis, Lauderic Caton, Ant and Dee Price, David Cooper, Dr Barber. Maple Leaf Garage, Olson and Son's Garage, Swain's Lane, Waterloo Park, University College Hospital antenatal clinic, Hotel Wetter in Paris, Avignon, Quartier Latin, Epping Forest, Hatfield House, the Paris Pullman, Jimmy's restaurant, Highgate West Hill, Kingston, Toronto, La Glace, Harmony Gates commune in the Kootenays. Valedictory: forbidding mourning, Streetcar named desire, Riverrun, Larkin Walking, Island, Scott Music for zen meditation, An anthropologist at work: writings of Ruth Benedict, Perls Gestalt therapy, Roy Campbell Autumn, Joseph Campbell Hero with a thousand faces, Through a glass darkly, Lessing's short story The other one, Une ou deux choses que je sais d'elle, Charlotte Painter Who made the lamb, Caton Brothers Ezekiel Saw a Wheel, Unified Family. |

[undated journal] Paris - wake up, I think Sunday morning, from a dream about a baby, mine, lying still looking at me, wise and serene, the most perfectly beautiful baby I'd ever seen. The dream left me very quiet. Roy said "Before you woke I was thinking about that, your baby." We're both uncertain, after having been certain. But I'm uncertain only of Roy's being uncertain. I'm becalmed, uneasy, guilty about my inertia. Paris, London, the Slade, theses, I'm not doing anything! There's nothing to do! I'm restless, I want to get on with something - and I want to be delightful. I am scared by how acutely I need to be delightful for Roy. I turn myself into him and understand exactly this: "Surprise me, delight me, teach me something, or you aren't worth my time." It's myself and it is also him; it's right, but it's precarious. Is that what's stilling me? When we talk I'm completely certain. More certain than he is, I think. I'm not afraid - maybe I am. There is nothing to be afraid of, only this becalming that leaves me without innovation, that's genuinely frightening. 28 April, morning The sister yesterday looked serious when I came in, and she told me to sit down. "The test was positive. That means you're pregnant." "Am I really?" and her puzzled look, "Yes you really are." "I'm so glad." "I'm glad you're glad. You're the first person here who has been." Out the door. Being glad, being apprehensive about Roy's reaction, feeling myself alone in the event. "I don't announce it because I don't want to scare you ... don't want you to leave ... think about all the time is whether I want to stay with you or not ... I have to think of it for two ... we'll always think about it." May I come in and am hurt to find him talking to Mafalda when we can't talk ourselves - I feel as tho' Mafalda has become the me who engaged him in the exciting public living room space where private conversation is a special gift timidly and thrillingly offered. We're sad. Last week he was very clear - he doesn't want the baby; he wanted to abort it. That reinterprets and deforms completely our weekend in Oxford - "I want to marry you, I want to have a child with you," his faith or courage and mine, transformed into foolishness so that my certainty becomes a wild leap into a new experiment, an exploitation of his impulse. The strangeness is very hard. I want to be one, a big mirrored hall for his memories and wonders and I want to feel as welcomed and recognized as I did. But we're troubled and uneasy; he's looking around and I'm longing for real privacy, our escape hatches just ajar in case we need them. [scrap of typed journal - not sure it goes here] "Such a hunger to be drawn out," such boredom, impatience, anger. Everything thin and unsatisfying. Boredom as being preoccupied, but by what? Grudging intolerance of conversations, ungraciousness, anger with Roy. The only things that are real are cooking and cleaning and sometimes sewing. I'm tired and crossed. Olivia's asking has made me realize how desperately bored I am. Grumpy thoughts of how limited people are, harassed thoughts of how I'm to cope with this dislike of everything. Depression like last September's after Peter. Feeling myself thinned down to insubstantiality. I've been getting thinner and angrier, trying not to and trying not to admit it, for a long time, since Munich and maybe before. Something souring, but it isn't Roy, it's me. Is it something to do with realizing - or fearing, I don't know which - that Roy isn't going to draw me out any more, isn't going to touch off play and language in me, isn't going to share all the childhood I want to share with him. I'm hurt when he doesn't listen to me. Two nights ago when he came in after being out all evening and came straight to cozy with Olivia without even saying hello to me, I was furious and so hurt I wanted to disappear. It seemed to me that I had nothing to look forward to with him, only more and more times when I come upstairs to find him silently holding someone. Don't know what to make of it, don't know what it means, don't want to leave, wonder if I'll ever feel myself again, wonder if he's ever serious about anything, wonder whether I'll get bored with him and whether it is possible to believe in him abstractly, with weeks and weeks going by without connection or spark. When he plays harem prince I'm not amused, and I don't like my own tight disapproval. The motorcycles don't amuse me either. His idleness makes me restless. He is out of love with me and I can't tolerate his distractions from that loss. I can't like anything else in him because that preoccupies me and I can't forgive it. I don't know what he's doing. We reassure each other, but we can tell the difference between reassurance and our touch-tone exuberance. I still feel how much is possible with him and how much would be possible if I interested him, if we could work at something together, if I became myself again so we could love each other without reassurance. I KNOW what it is like to be so sure of him that I don't care who he holds and who he titillates. It was being sure that we recognized each other and were extraordinary to each other. If it isn't that, if it is going to be nothing but banal struggle for tolerant acceptance, there's no point in it, child or no child. Struggling to adjust is all wrong. How long will it take to know? A Thursday It becomes clear sometimes - I had a dream the night before last in which I explained to myself lucidly, articulately and very calmly exactly what Roy is. I remember my even tone of voice but I remember very little of what I said. I think it was no more than what I know that I know. The morning we woke in Amsterdam, after I'd calmed myself out of the sobbing evening before by thinking of the reeds along the canal tipping in the wind like waves, we fought about the baby for the first time. He claimed that he had not said what I remembered him saying, that he wanted to marry me and wanted a child with me. I found myself screaming with grief, because what I remembered as our joyful and mutual leap seemed to be deformed in his memory into a stupid and gullible mistake I made, on my own, and using him to make it. I don't want to take my child away fatherless before it's even born; I don't want to make Roy a deserting father; I don't want to live on and on exhausted as I am; I don't want to struggle not to love him. As I've been getting thinner and more desperate, he's become gayer, more beautiful, more playful, more confident. When we lived in the flat before, with Ian there, I didn't find him beautiful. He wasn't playful, he was very silent, sad, serious. The flat was silent. We were chaste; he was shy. When I let myself go with him it had nothing to do with his beauty, charm, energy, flirtatiousness, daring - it was only the joy I felt when I talked to him; his life, his intelligence, his feeling. Where has this terrifying child come from? This vindictive happy indestructible caterpillar, is it me sustaining it? Where's the lever that overturns the structure and lets me breathe for a while? Is he worth the terror? No, of course not. And our child, for whom my imagination turns in and out of all the complexities of geography, ethics, education, relationship? Tuesday, Paris [undated journal] Hello little baby (lit-tle ba-by, R's voice). I've come here to remember what it was like to be alone, before Ian and Roy; partly I want to be alone with the little baby I can still hardly believe is there (although my skin crushes like suede and my womb is nearly up to my navel). To see whether I can cure myself of the terror of the last four and a half months. Avignon Sunday Woke up in the youth hostel and my first thought was "I know it's finished with Roy." I'm full of grief these days. The night before I left Paris, the electricity went off and I lay awake most of the night with my body pinching me grief all over, crying "It's horrible, it's horrible" and burying my face in the little blue sleeper I bought that day ("Qu'est-ce que vous avez pour les nouveaux-nés?") I'm so hungry and sad and I'm so choked on Roy that it's angry bad tasting sadness much of the time. - At Porte d'Italie the bus driver told me the autoroute was closed. I stood on the pavement wondering where to go. A blue transport truck with a long trailer turned into the Avenue de l'Italie, carefully around the corner, I looked at him, just looked questioningly, and turned to see him pulling up. "Ah! Vous avez de la chance!" He was going to Lyon. Apologized for not speaking - "Oh non! J'aime ça." Bit off all my fingernails with excitement, reading the Gestalt book sitting under a tree beside the shingle factory waiting for the truck to be loaded. Lunch, a little watered wine and I rushed to tell him about my baby, about going into the store and blurting the "Qu'est-ce que vous avez pour les nouveaux-nés" I'd rehearsed in front of the all the windows. He's small, hard, brown and shiny in his undershirt and shorts and sandals. His silences are good, he doesn't say anything stupid. I like his strong legs and his expertise with the truck. He says he's 47 and has a grandchild. He won't flirt but he smiles. I soon feel safe enough with him to look at him. Outside of Blois we take a detour down a narrow straight road with forest close in on either side. At the end of the road, towers, and walls, and a castle more beautiful and elegant than we could have imagined, sitting flat on the same level as the road, like a mirage. Past the castle another narrow road, pine trees and their smell, but something else too, a wonderful strong smell of spices. He stops the truck and we jump out to locate the plant - but it isn't the stiff purple bunches, and we can't find it, but he's on his hands running along the ditch smelling the plants on the ground. Night, he stops for an hour's sleep, I lie in my sleeping bag in the grass beside the truck, big white stars, some slipping. Trucks roaring and fading, the sound of stars. Sleeping in the couchette, the jolts to my breasts and belly easier lying down, curled around my sleeping bag with it wrapped around my head, waking early to see pink sky and alpine foothills, the South, and dusty golden farm buildings, faded orange tiles, deep valleys, hills roaring out of them. A handshake at Lyon and he's gone, smile like a proud father. Paris Sept 13th What I see in shop windows - myself as a little pregnant Charlie Chaplin, round hat, long plaid shirttail, pant legs flopping over little sneakers, and an expression of self reliant apprehension in the turn of my neck and the shape of my back. Pathetic little feet, clothes all too big, shaming those neat silly little feet in their black and white sneakers. A little person, completely desexed and shapeless - even my big belly gets lost in the lumber shirt. The worry lines on the forehead, intelligent eyes and mouth, disapproving, appraising. 23 September We walked into Epping Forest and lay down to sleep on a drier ridge among the beeches, on a slope with sun. I looked at a fern holding itself against the light, at a rose-and-brown fuzzy toadstool, tiny leaping insects, beech leaves that were dirty brown scraps until I held them against the light and found green, gold, tea-coloured radiant mosaics with holes to show through to Roy's blue jacket. Fell asleep, woke to find I'd been stroked peaceful by the place, sunlight warm and cool at the same time, leaves dropping singly and occasionally with a slight crackle when they land, grass in a brilliant tuft along Roy's thigh, planes of beech leaves green and turning stretching high and then far away, a momentary revelation of how unlikely and how wonderful it was to exist. I thought, "I must let the child know about this." And Roy's warm self to roll up against - even if it's out of love with me again. [undated October letter] Since we've come back we've been very close and happy. I hold my breath and daren't expect it to last, but maybe it will last for a while. I like him more than ever, and feel myself dangerously lucky. The child has grown just in the last two weeks - now I "wear my apron high" and have begun to alarm shopkeepers in Kentish Town by continuing to ride the bicycle. Sunday, 1 November We fall asleep with the child between us, kicking against Roy's back. Later in November, Saturday night Rain, the sound of wet cars sooshing through the water on the street, rain rattling on the window like sleet, wind, the screech of a bus turning at Swain's Lane, lights on Highgate Hill seen through the drops and running scribbles of rain on the window pane. Lauderic downstairs playing with electrical testing equipment, watching television. Roy - We drove through the rain to the Paris Pullman to see Une ou deux choses que je sais d'elle. Although it was only a little after three it was almost dark, and the lights had begun to shine on the pavement. Shots of the whirling galaxies and bubbling black outer space of café and Coke; Marina Vlady looking sideways at a man in the bar while Godard's voice whispers that since we can neither rise to being nor sink into nothing, we must pay even more attention to where we are, to the world, to our semblables, our frères. Roy striding in his high boots and tight pants and elephant coat, hair washed. Friendly presence, putting off explosions until someday. Rain rattles even harder, cold air from somewhere. I'd like to take notes on our life these days, but don't and don't really want to. I'm waiting, not only for the child. I'm big, heavy on the stairs, healthy, almost serene. I look forward. I have trouble thinking of work although I know I must find a way to support myself and use myself. Roy is a mystery and a wonder, I don't know what to do with him. I feel that he's some part of my life come to a peak, filled out, filled in, fulfilled, a climax, a meeting. Several weeks ago Roy came home from the motorcycle repair shop delighted with a man he'd discovered in the yard, Lauderic Caton, a black Trinidadian. A few days later I came home to find Lauderic with Roy in the living room, playing old records and telling stories about his long life. At first he reminded me of Uncle Willie, merry and opinionated in the same way. He loves to talk and chokes with laughter at everything any of us say. He's been a famous classical guitarist and has played and arranged for jazz bands in the 40s. He's written a symphony. He's invented a new kind of guitar. He studies Latin for his own pleasure, has a set of primers that he gets through once every couple of years before beginning again. He was in Paris during the '30s, in London during the war. Now he works part time making packages for St John's Ambulance, drives about on an immaculate white Honda, studies electronics in his attic flat at King's Cross, professes to love solitude but finds excuses to come see us. He looks thirty but is really sixty, wears a light grey suit suspendered up under his armpits, a bow tie, a black beret to cover the little distance his fuzzy hairline has receded. One of the records he brought over was the Caton Brothers singing Ezekiel Saw a Wheel ("We're all black, man, so they think we brothers") - Lauderic's complicated '40s arrangement and Lauderic singing a bass that would make Father shiver with delight. When I told him about the baby he said "Oh that's good, that's good!", offered to babysit, advised me to hold onto the rail when I go down stairs, demanded to know whether we'd chosen names and ordered us to find something unusual, "Jus' take some consonants and some vowels and make something up." I don't know whether I've told you about Buddy Hardy, the old woman who lives up the hill from here. She's seventy and very nearly blind, but smart, wise, adventurous and all alive. I picked her up on the subway one night just after Christmas. She came in looking so radiant and so intelligent with her thin frail strong body and her wrinkled old face and her opaque eyes that I had to know her. And then to discover, at the bus stop, that her name is Buddy Hardy! She was a South African like Roy, became a midwife, worked in Malaya and East Africa, took all sorts of courses, was a labour organizer in South Africa and was honoured with a one way exit permit because of it (ie expelled from the country). I took her up the hill one day to show her a beautiful empty house in its vast overgrown secret garden. Yesterday on the telephone she told me she had gone back to pick some bluebells on her own. Two dogs had come snarling at her from next door, "I couldn' see them of course but from the sound of them they were as big as great Danes. Just by chance I began to sing, and that held them until I could feel my way to the fence, but I couldn't find the gate, so I climbed on top of the fence, but then I couldn't see how far it was down to the pavement" (she can't even see how far it is from the curb to the street), "so I hung on until two children came by. I handed them the bluebells and said 'Take these and help me down!' And then I came home." Nov 27th Roy is so sick. He feels close to death and I also feel the fragility of life in his thin sore body. I'm confused, want to lend him myself to be whatever he unpredictably needs, am afraid for him, am angry when he seems not to want me, bring him all my old nonsense of fear and pride, am ineffectually warm and ineffectually cold, want to be left in peace to pay sentimental attention to these last few weeks; he's impatient with me, solitary, hard to please, loving, courteous, distracted. I miss him. December 9 When your letter came this morning I was stretched out naked on a mattress in Roy's sunny room being photographed by Mafalda, who was all excited about abstracts she was getting of my big round middle - it is huge now, tight (but no stretch marks!) so the belly button bulges. The creature is lying curved around with its spine on the left side - I can feel the hard head shape if I poke. It's winter now, no snow, but the wonderful swift heavy winter north skies are full of wind and mist. We've had electrical strikes in the last few days, thrilling stretches when there were no yellow streetlights, no traffic lights, no shop lights, no heating, no cooking, no TV, just candles flickering under stars, R and I gleeful under the featherbed listening to carols on the transistor by lamplight and imagining all the supermarkets with their frozen food turning into puddles, chaos at every intersection, factories shut down, thousands of people sitting down to cornflakes for supper.

|